Tragedy On The Gridiron

The injury called to mind a darker day in Georgetown's long history of football, Nov. 28, 1894.

In only its seventh year a a true intercollegiate sport, Georgetown often lacked local college teams to play. By the early 1890's,Georgetown was one of just three local colleges playing football, along with Gallaudet and the Maryland Agricultural College. (A fourth, Howard, had just started football but was limited to all-black schools by segregation laws.) Georgetown's rivalry game was with Virginia, but a budding local series had emerged in the Columbia Athletic Club, located in Northwest Washington at 815 15th Street, N.W.

Formed by members of the business and government sectors, the club numbered 750 by the turn of the decade, and initiated a series of eight sports teams, with a football club in what would be more likely called a semi-pro outfit by today's standards. Members of the club's team were a variety of local workers and athletes, many older than college age and with no specific educational attainment to have reached.

"The objective of this Club is to encourage all manly sports, promote physical culture, and social purposes," read its constitution.

The latter took hold in its nascent series with Georgetown. Crowds flocked to National Park, the home of the professional baseball team of the same name, for the annual games with Columbia and Georgetown, selling out the 6,500 seat structure. Lacking any scheduled sports in the area after baseball season, college football was the social event of the fall, and the Thanksgiving Day games between Columbia's Red & Blue and Georgetown's Blue & Gray were given front page treatment by each of the city's four dailies.

Early games in the series had taken on a genteel air by most accounts. Columbia won the first two of three, with Georgetown taking a 12-0 upset in 1892. The 1894 game, promoted as the greatest game yet between the teams despite a 4-4 record by the Blue and Gray and 3-6 for Columbia, saw a record crowd of 7,000 fill National Park, the largest crowd ever to witness an athletic contest in the city. It also attracted a run of visible wagering, with odds not only on the outcome, but when key players would be knocked out of the game.

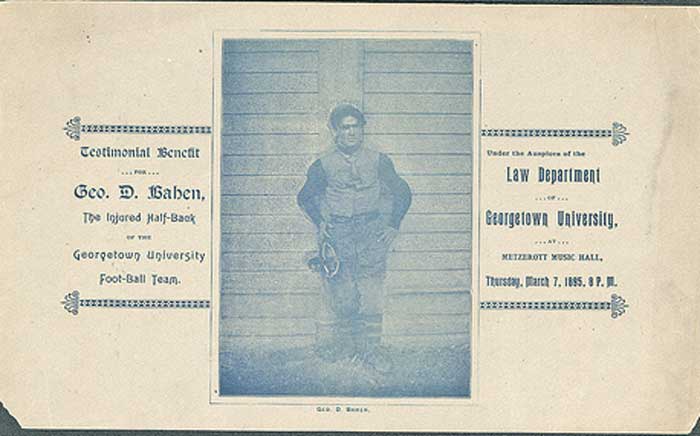

It was no secret which Georgetown players were in the gamblers' sights. Player coach Bill Carmody, a medical student and veteran of the early Georgetown teams of Tommy Dowd, had returned to the lineup to add strength at quarterback. His two running backs were well known in local circles: George "Big Mike" Mahoney and George "Shorty" Bahen.

At five foot four, Bahen was small relative to today's standards but decidedly average in the heights of the day. The average U.S.-born male stood just five foot, five and one half inches in 1890, but as Bahen was the shortest on the club (with just two players taller than six feet), the nickname stuck. Bahen was a tough ballplayer across the board, and engaged in Georgetown's version of the goal-line offense. With the forward pass more than 10 years away, a scoring drive in football necessitated a scrum formation. Georgetown devised a play where Bahen, trailing Mahoney in the backfield, would be catapulted by the 6-4 Mahoney over the end line, a certain fan favorite, and a difficult one to stop in short yardage offenses.

Bahen's high-flying moves were well known by Columbia, and an obvious target of its aggression.

"According to accounts of the day, the betting gentry on lower Ninth Street were taking wagers on how long it would take for certain key players of both teams to be knocked unconscious, or completely disabled" wrote Morris Bealle in his 1947 history of Hoya football. "The particular targets of many of the Columbia bettors were Bahen, Carmody, and Mahoney. One could get great odds if one chose to bet that any of the trio would last more than 20 minutes."

Game time was 2:00 pm on Thanksgiving Day, 1894.

Georgetown kicked off to begin the game. Columbia drove to midfield but no further, and Georgetown took over for its first drive five minutes into the quarter. Two runs advanced the Blue and Gray to the Columbia 20 and the game took an ominous turn. On first down, Bahen's head was cut open in a tackle. Sent to the bench, he was taped up and prepared to come back in when, on second down, Carmody was kicked in the head and fell unconscious. After Carmody was sent to the bench, Bahen returned on third down. Reports do not show Bahen carried the ball, but in the scrum two things happened: he was speared in the stomach and, while on the ground, someone forcefully thrust his foot into Behan's back, fracturing his C5 vertebrae and rendering him paralyzed from the waist below.

"Bahen, Georgetown's plucky little half back, lay white and motionless on the ground," wrote the Georgetown College Journal. "In assisting Mahoney's play he had come into collision with Leete, and was met by the latter's head planted in his abdomen or stomach...It is said also that that he was struck twice, and that after he was down one of his opponents kicked him in the back, while another jumped upon his prostrate form, planting both knees upon his stomach. However this may be, it is certain that after the mass of players was disentangled, he was found to have sustained severe and probably fatal injuries."

In modern times, such an injury requires a specific protocol to immobilize the victim, avoid shock and limit motion in the affected area. The efforts in the first moments following Ty Williams' 2015 injury were essential to his prognosis and his ability to survive the surgery. Such protections were altogether unknown in 1894, especially at an event where there was no trained medical personnel reported at the game. Instead, six players lifted Bahen, still conscious but in severe pain from the fracture and the stomach injury, onto a horse-drawn wagon which was dispatched to the campus infirmary for observation.

The game continued with more violence. Mahoney was knocked out in the second quarter, but recovered. The first half ended in a scoreless tie, and fans from both teams poured on the field to trade songs and insults between each other.

Columbia opened the second half with a touchdown but the violence continued. Georgetown's Sam Boyle was carried off the field with a leg injury. GU's Paul Callahan took matters into his own hands, striking a Columbia player in retaliation and setting off a bench clearing brawl that led the local police onto the field to restore order.

"The crowd became unmanageable on the south side and the police were unable to preserve the lines," wrote the Evening Star. "The spectators surged onto the field and interrupted play."

Columbia took a 14-0 lead midway through the third quarter and went on to post a 20-0 win.

The game had scarcely ended before it was on the front cover of that day's Evening Star. Since little was known about Bahen's injury, the incident was given scant coverage, focusing instead on the crowd which gathered for the game.

"They were all on hand, the long haired youth with the latest cut of voluminous overcoat, and the beribonned cane; the pretty girl with the chrysanthemum and her favorite colors, the exuberant young men with bellow-like lungs, and sometimes with a tin horn accompaniment," it wrote. "So too the pretty girls, who gave to the field the appearance of a great posy garden. Their cheeks were red with the snappy air and the excitement, and the attendant blue and grays were to be found in their eyes."

The reports the following day were far more grim. "BAHEN PARTIALLY PARALYZED", read the front page story in the Washington Times.

"Drs. Kerr and Kleinschmidt who are in attendance on the case, held a consultation yesterday, and stated [Behan's] spine was injured, but could not determine the exact nature of the trouble," said the Times. "Bahen's stomach and the muscles in the region of the abdomen are paralyzed, and if he should recover he will be permanently crippled. He was conscious last evening and cheerful, although suffering intense pain."

With the present Georgetown University Hospital still four years away from its founding, Bahen was relocated to the Washington Emergency Hospital for exploratory surgery a week after the game. The doctors sought to relieve pressure on the spinal cord but realized there was nothing further they could do. Stories that Bahen was near death appeared in the dailies, while a judicial inquiry was proposed to determine if criminal liability existed among those Columbia players at our near the scrum, a sensitive issue given the prominence of many Columbia club members in Washington business and society.

Paralyzed, unable to digest food, and overwhelmed in pain, Bahen survived for four agonizing months in the hospital. Students visited daily. His father, a Richmond city alderman, moved to Washington to be at his side. The law school held a fundraiser to pay his medical bills.

On the very day the city announced it would not pursue criminal charges were dropped against the Columbia team because attorneys could not identify an assailant, George Bahen died on March 28, 1895, emaciated from four months of paralysis. According to Bealle, Bahen's final words were:

"If it's God's will I go this way, then I am ready."

Bahen's body was returned to the University, where students carried his casket to Holy Trinity Church for funeral services attended by the entire student body. A delegation accompanied the body by train to Richmond, where the family held private burial services.

While it was not made official until September 1895, the College faculty voted to end participation in football due to the unrestrained violence found in the game. When a change of administration in 1897 returned the sport, it did so with one visible change: Columbia, and athletic clubs like her, were no longer on the schedule. Georgetown would only play collegiate opponents from now on.

"Shorty was one of the finest and best loved lads of the day," wrote Paul Burne (C'1900) in a 1958 letter to the University. "His death caused a gloom for a long time." Burne may have been one of the last living alumni to have known George Bahen, whose story now exists only in a few photos and forgotten newspaper clippings, but little else. George Bahen was among the first college players to die as a result of football injuries and his lesson is a cautionary one, but one of hope. His was a story of playing with purpose, and fighting to the end.