Salad Days

By the fall of 1946, Georgetown had resumed its intercollegiate football program after a three year absence during World War II. As an entire world had changed since days when the Hoya Band was proudly marching into the Orange Bowl, the landscape of college football had also changed.

During the 1930's, many of the nation's top football programs had been private schools. It was not uncommon to think of Carnegie Tech, Fordham, Dartmouth, or even Columbia as national contenders, nor was it unusual that smaller schools like Catholic, Gonzaga, and St. Mary's actually appeared in major bowl games. Only a small percentage of men between 18 and 22 actually attended college during these years, and those that did were attracted to the nation's leading academic programs.

Following the end of the War came the G.I. Bill, bringing thousands of young men to college campuses. While many of these students enrolled in private schools like Georgetown, sheer numbers sent most to land grant colleges, causing a boom in their enrollment. Football programs began to flourish on state campuses, and with it the crowds necessary to finance major college football. Those that grew, flourished. Those that stood still, stepped aside.

The story of Georgetown's last half-decade in major college football are increasingly subjective, as the march of time winnows away those who were a direct part of it. Nevertheless, those who chronicle it are prone to a subjective view.

If all one learns about Georgetown's football history of the 1940's is from the bicentennial history of the University as written by Robert E. Curran, who used words like "disaster" when describing the team's fortunes, they would be found wanting. Jesuits are loath to criticize their brethren, and while the official historian paints this era as some sort of moral elevation of the University from the woes of intercollegiate football, Curran's narrative reads as more of an affirmation of football's demise than an objective view of Georgetown's strategic failure to support football, and the results which it wrought.

Consider this another view.

Jack Hagerty returned to civilian life in 1946 as a distinguished Naval officer and a distinguished college coach. He had offers to go elsewhere, including the NFL, but returned to his alma mater to restore football to the Hilltop, four tears after the program was mothballed by World War II. Gone were the giants of Lio, Castiglia and Blozis; fewer of the men of 1942, their lives forever changed by war, were quick to return to a college gridiron. Hagerty acquired a mix of returning GI's and post-war collegians for the 1946 season, a group he was not altogether comfortable in, as referenced by a 1966 interview.

"Before [the War], the school was smaller. You knew everybody," Hagerty said, "After the wars it was enlarged with the G.I bill and boys were taking from the school without trying to give anything in return."

In ten seasons, Hagerty had taken a program stripped of football scholarships and built it into a program competing in the Orange Bowl and drawing 25,000 to Griffith Stadium against the likes of West Virginia, Syracuse, Mississippi and Auburn. In 1946, he would start all over again.

Georgetown's steady climb up the ladder in the 1930's had been built on scheduling: a mix of lower division fodder for early wins (Delaware, Mt. St. Mary's, even the likes of Roanoke and Shenandoah College), some of the larger Eastern schools (Temple, Syracuse, NYU), and familiar Catholic peers such as Boston College and Fordham. The only larger, state-supported school which Georgetown regularly faced was Maryland, where Hagerty had outperformed the likes of coaches Frank Dobson and Jack Faber, winning five of the last six meetings with the Terrapins before the War.

The post-War schedules as constructed by Georgetown's faculty athletic director Matthew Kane, S.J. was in hindsight, puzzling. Georgetown would be sent on the road to places like St. Louis, Tulsa, and Denver, to which athletic rivalries were non-existent, while as few as two home games a year would be scheduled at Griffith Stadium, along with a third game with George Washington where the gate would be split. Kane was not only athletic director, he was the University treasurer, and may have been mindful of the rental costs the stadium foretold. When games were held at home, they were well supported: the 1946 team averaged 16,185 per game, a larger number today than any men's basketball season since.

Another puzzler: home games were moved to Friday nights. While Saturday afternoons were the domain of the college game, Friday was an anomaly, with scores often missing the Saturday morning papers and all but forgotten by the Sunday papers that sung the praises of various heroes across the Saturday landscape.

Rev. Kane also scheduled schools to which a 1945 schedule was already in hand, making it tougher for the Hoyas to play catch-up after the University had opted not to return to the sport in the fall of 1945. The Hoyas would have been wise to reopen its football fortunes with a Delaware or even Richmond; instead, Kane scheduled the season opener in 1946 against 19th ranked Wake Forest, coming off a 1946 Gator Bowl win versus South Carolina and a second place finish in the Southern Conference. Hagerty's team wilted in early-season practices and the active squad diminished considerably by the opener, where the Demon Deacons won 19-6. By the third game of the season, Hagerty was down to his fourth string quarterback; by mid-season, Hagerty had roughly half his fall roster to travel to games in St. Louis and Boston.

"Entering the game a 40 point underdog, the Hoyas passed their way to victory," wrote the 1948 Ye Domesday Booke. [Quarterback Elmer] Raba using his pitching arm tossed the first TD, a pass to [John] Kivus, who was waiting with open arms in the end zone. Fading back again in the closing seconds of the first half, Raba uncorked his right arm passing for a score, this rime to [George] Benigni, the Hoyas' towering flanker. Holding the upper hand throughout the game the Blue and Gray kept the Golden Hurricanes bottled up in their own territory throughout most of the game."

As Georgetown stumbled to the conclusion of the 1947 season, others were stepping up. After a string of middling finishes, Maryland hired Jim Tatum, fresh off an 8-3 season at Oklahoma that produced nine All-Americans. In his first season, Tatum guided the Terrapins to a 7-2-2 record and the school's first ever post-season bowl, losing to Georgia in the Gator Bowl. In a nod to a changing era in local sports, Tatum moved his Nov. 19, 1947 game versus #17 North Carolina from the former Byrd Stadium (which sat just 10,000) to Griffith Stadium, the home of the Hoyas. A crowd of 22,000 came to watch the game, larger than any Georgetown crowd in five years.

By 1948, Maryland announced plans to raze its old field for a modern Byrd Stadium, which would become the largest college facility north of Atlanta. In the interim, Maryland moved its entire home schedule into Georgetown's back yard, averaging over 25,000 per game in the process. The Hoyas' home schedule that season was unremarkable, with games against Boston College, Denver, and NYU, the latter of which drew just 5,892 to the stadium, the smallest home crowd in a over a decade.

On the field, Georgetown was a team which had seen better days. Despite a caravan of 700 students who traveled to Georgetown's first appearance in Fitton Field since 1937, Holy Cross wore down the Hoyas in an 18-7 finish, followed by a similar outcome versus BC, 13-6. The Hoyas rallied with three wins and a tie to make the case for a five win season at season's end, but were outclassed in a 37-6 loss to Villanova at Shibe Park. Ralph Pasquariello, a future first round NFL pick from the Main Line, rushed for three Wildcat touchdowns by halftime.

Hagerty's nadir came a week later against George Washington. The Hoyas had not lost to the Colonials in the entire series which stretched to 1898, though a 0-0 tie in 1947 was a cause for some concern. The Colonials entered the game after a 62-0 thrashing by Duke a week earlier and, at 4-5, had little momentum as well. But a 7-6 Georgetown lead in the fourth quarter collapsed when GW's Bill Szanyi blocked a Georgetown punt at midfield and raced 45 yards for the winning score.

"We did not know it then, but the George Washington disaster heralded the climax of a football era for Georgetown," wrote the College yearbook. "Shortly the Hilltop would reverberate with changes in the athletic department. Rome Schwagel resigned his position as Athletic Director, to be replaced by Jack Hagerty. Mr. Hagerty was succeeded by Bob Margarita. His assistants. Mush Dubofsky and George Murtagh were swept up in the shuffle. Mush resigned as line mentor, while George became coach of freshman football."

Hagerty's pleads to downsize the program fell on deaf ears. Even as coach turned athletic director, he relied on the Jesuits to make the decisions on the program.

"I had proposed a league three years ago and thought it would be the salvation," Hagerty recalled. "I didn't want a Catholic league but one of Fordham, Boston College, Holy Cross, Pittsburgh, Penn State, Temple, Colgate, and Georgetown." It was not pursued.

"One time at an alumni meeting the men were yelling for 60 scholarships a year. I told them you're going to kill the golden goose. We gave 20 grants a year then." Instead, Rev. Kane endorsed a plan for increased scholarships beginning in 1949.

Two decisions imperiled football at the close of the decade. Hagerty's successor, Bob Margarita, had never held a head coaching job before; he assumed the job at Georgetown at the age of 28 with one season as an assistant at Harvard. Of greater impact, the term of Rev. Lawrence Gorman, S.J. as University President was not extended, and Rome's choice was an abrupt departure with that of his predecessors.

In a span of just over three years from 1949 to 1952, J. Hunter Guthrie, S.J. served the shortest tenure of any President of the University in the 20th Century. A divisive, combative figure, Guthrie will instead be forever linked with Georgetown athletics--the man who ended major college football.

Guthrie was just 47 when he was named president, after five years as the regent of the Graduate School. He took over as presidents following a post-war University boom that had nearly doubled the University's enrollment since the end of World War II. An avowed intellectual, he saw the Graduate School as being outmuscled by Georgetown's other schools--among them, medicine, law, and foreign service, none of which held to his view of graduate education as the highest, noblest purpose of a university. Athletics was, at best, a diversion from this learning and, in some of Guthrie's later views, a threat to it.

"Each individual in his growth to maturity undergoes in a microcosmic manner the intellectual development of the world," said Guthrie in an arcane inaugural address as president in 1949. "Thus the patiently cooled truths of pagan antiquity, beautifully encased in the literature of Greece and Rome, were saved and used as a propedeutic for the student's maturing mind to fathom the mysteries of Redemption."

More to the point was his premise of governance: "Idol worship, in the sense of pursuing shadows and deferring to opinions, is a modern disorder."

Put in simpler terms, Guthrie had no patience for consensus. Such is what awaited football following the 1950 season.

For his part, Hagerty left Margarita with a full plate of player options for the 1949 season, including All-America RB Billy Conn. Conn led the Hoyas to wins in four of its first five games, with the lone loss to a Maryland team which would finish 9-1 and win the 1950 Gator Bowl. Of note: Georgetown played only one home game in this run.

The second half of the schedule saw a strong effort from QB Frank Mattingly, but the Hoyas dropped games to Fordham and Villanova. One November 19, 1949, the day before its season finale with George Washington, Georgetown was invited to the 1950 Sun Bowl, against what was presumed to be Texas Tech from the Border Conference. Georgetown enthusiastically accepted the bid, but neither the University nor the Washington dailies took note of the circumstances surrounding the Sun Bowl's bid.

A year earlier, the Sun Bowl invited Lafayette (7-2) to play Texas Western (now Texas-El Paso), but under the condition that Lafayette's lone black athlete, running back David Showell, neither play in the game nor travel with the team. Following a large campus demonstration in support of Showell, Lafayette declined the bid, and Sun Bowl officials reluctantly reached out to West Virginia to fill the bid, inasmuch as West Virginia was an all-white team. A year later, Georgetown also fit the bill and would not bring up the issue of playing within a segregated bowl game. Apparently, it did not.

A day after the announcement, George Washington spoiled the celebration, 28-7, but the Hoyas were otherwise bound for El Paso and their first New Year's Day game in nine years. Following Texas Tech's decision to accept the Raisin Bowl bid instead, the hometown Texas Western team returned to the bowl game and defeated the Hoyas 33-20 at its home stadium, Kidd Field. If there was a financial payout, it was quickly absorbed by the travel and did nothing for the revenues back home.

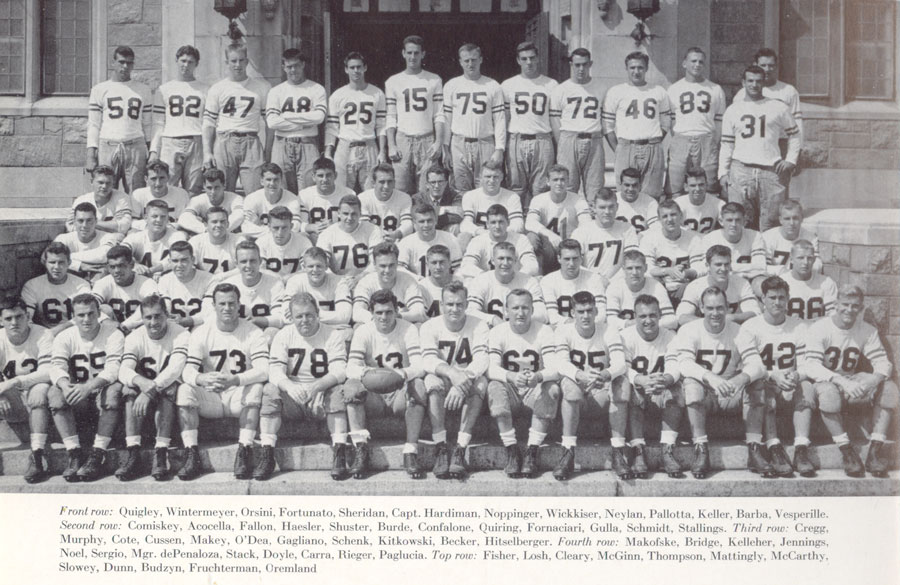

There were no bowl games in store for Georgetown in the fall of 1950. Billy Conn announced plans to transfer to Auburn, while a number of Hagerty's recruits had reached the end of their eligibility. In total, the 1950 team would welcome 38 newcomers among the 64 roster slots on the team, and the situation was complicated by an even more aggressive scheduling posture by Georgetown. Gone were Wake Forest, Denver and NYU, in were Penn State, Miami, and Tulsa.

The Hoyas opened the season on Sept. 30, 1950 at Beaver Stadium, in what was Joe Paterno's first game on the Penn State staff. When the season ended nine weeks later on November 25, Georgetown suffered its worst season since 1905 at 2-7, with an attendance average of less than 6,200 per game.

Sensing trouble, coach Bob Margarita attempted to change course by announcing a revised 1951 schedule--instead of schools like Penn State, Miami, and Tulsa, the Hoyas would schedule Richmond, Bucknell, and Lafayette. Talk of a non scholarship program similar to the Ivy Leagues was floated as a way to save costs. But as the financial reports came in, the program was in trouble.

Georgetown continued to see deficits within numerous academic and extracurricular departments, including athletics. Football was a regular problem, as revenue was entirely based on walk-up ticket sales at Griffith Stadium. The 1950 season aroused Guthrie's ire, because the $140,000 budget allocated to football returned just $44,123.97 in tickets, with attendance down a third from its Sun Bowl season the year before. There was no annual fundraising within the University and certainly not for football.

Following the 1950 season, Guthrie took over the athletic department's books to get a look at the financial ledgers previously under control of Rev. Cornelius Herlihy, S.J. Drawing upon the onset of the Korean War to claim a risk of significant downturn in enrollment, he proposed ending the football program to the Board of Directors at its spring 1951 meeting. Largely ignored in accounts of this decision was exactly who the board of directors were. Unlike their counterparts today, representing a mix of executive, philanthropic, and educational interests, the Board of Directors in 1951 were all members of Georgetown's Jesuit community, to whom Hunter Guthrie, as Rector-President, held both temporal as well as spiritual leadership over them. Publicly opposing one's boss might be dangerous, but opposing one's spiritual superior was something even more serious.

In football, Guthrie may have been less concerned about sports and more interested in the bottom line. Guthrie took heed of a consultant's report by Tulane University comptroller Clarence Scheps which read, in part, "Every sign points to a very difficult period ahead in college administration. Institutions of higher learning are going to be in grave financial difficulties especially those like Georgetown University which are dependent almost entirely on tuition from students for their support.

"The values which Georgetown University has bestowed upon the culture and education of our country must not be permitted to be lessened or endangered by a loose and inefficient fiscal system."

On March 22, 1951, Guthrie proposed the sport be dropped immediately. The board voted unanimously to accept the Rector-President's recommendation.

Headlines nationwide proclaimed "GEORGETOWN DROPS FOOTBALL." Certainly, other schools had abandoned the sport, but this was the most prominent university to leave big time football since the University of Chicago dropped out of the Big Ten after the 1938 season. By the fall of 1951, 38 universities had dropped football, none more notable than Georgetown.

Students were on spring break. The HOYA did not announce the story until April 11, where its headline "Georgetown Drops Football" was placed aside the tragic death of three students in an airplane crash. Student disapproval was also tempered by the times--publicly questioning the decision of a Jesuit president in the 1950's would be grounds for expulsion.

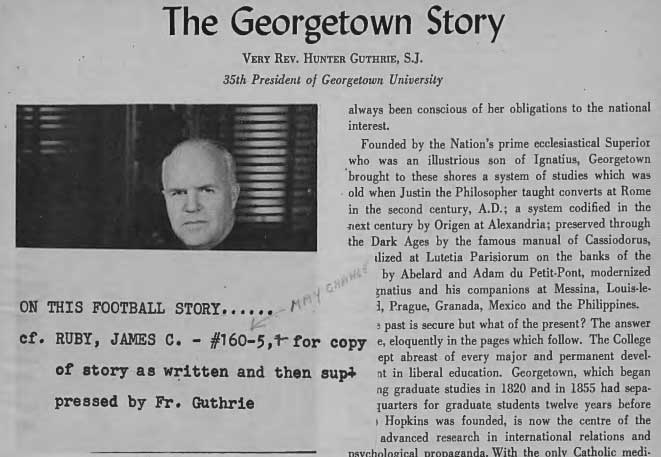

Alumni were under no such clerical restraint, however, and many were bitter in their responses. While Curran's book held that "alumni reaction was mostly positive", it was anything but. An article in the spring 1951 Georgetown University Alumni Magazine to discuss the decision was listed as "suppressed by Fr. Guthrie" (a pre-Vatican II term for censored) in a pre-press copy of the issue. In place of letters from concerned alumni, a series of over 15 pages of biographies of various University executives followed, led by an ornate academic treatise on the glory of Catholic education written by Guthrie himself. If alumni were waiting to see their thoughts about football in print, they saw this instead:

"Founded by the Nation's prime ecclesiastical Superior who was an illustrious son of Ignatius, Georgetown brought to these shores a system of studies which was old when Justin the Philosopher taught converts at Rome in the second century, A.D.; a system codified in the next century by Origen at Alexandria; preserved through the Dark Ages by the famous manual of Cassiodorus, revitalized at Lutetia Parisiorum on the banks of the Seine by Abelard and Adam du Petit-Pont, modernized by Ignatius and his companions at Messina, Louis-le-Grand, Prague, Granada, Mexico and the Philippines."

The letters were never printed. In its next issue, the editor remarked that "On March 22, 1951 when the University announced the end of Georgetown's participation in intercollegiate football, much of the mail and verbal comment we received expressed the conviction that for one reason or another the Alumni Association would either suffer severely or fail altogether."

Had Guthrie reserved further comment and moved on, the loss of football might have been portrayed as a casualty of wartime. But the Rector-President would hear none of it. He wrote a stinging rebuke to the alumni community in a lengthy 4,000 word essay published in the October 12, 1951 issue of the Saturday Evening Post in which he served to indict the sport and those involved with it.

"Into football," wrote Guthrie, "goes a stupendous outlay of time, money, and manpower, accompanied by the raw passions of greed and slavish devotion, the ignoble emotions of spite, bitterness, and sly cunning." His college would have none of it. "We did not want the clean, patrician features of Georgetown disfigured by a broken nose and a cauliflower ear", he wrote.

(Remarkably, the article is not available anywhere online, owing to the policies of the Curtis Publishing Company, owners of the Saturday Evening Post, which does not publish its extensive archival content online. A request to post the article on this site was rejected by the publisher.)

There is a body of opinion that suggests Guthrie's major decisions during this period, including football, were part of a larger battle within the University itself. As regent (dean) of the graduate school from 1944-1949, Guthrie had fought for funding alongside three other Jesuits at Georgetown (Edmund Walsh, regent of the School of Foreign Service; Francis Lucey, regent of the Law School; and Paul McNally, regent of the Medical School), without much success. Washington attorney Terrence Boyle (F'63) contends that Guthrie's decisions were a larger attempt to centralize control over the regents' spending.

Boyle noted that the School of Foreign Service under Walsh existed autonomously from the main campus, and had developed its own operating budget and fundraising, of no small irritation to Guthrie while he served at the forlorn Graduate School. Across town at the Law School, Curran's book speaks to Lucey's vocal opposition to Guthrie's policies as president and that Guthrie had formally requested permission from Rome to fire Lucey outright. According to Curran, the Jesuit superiors in Rome had "chastised Guthrie for his manner of governance" and withheld funds for a new dining hall Guthrie had championed as a result.

Boyle's web site makes two interesting claims:

1. The McDonough Gymnasium project, proposed as an annex to Ryan Gymnasium as late as 1949, was unilaterally moved by Guthrie to the site of a future SFS building. "Fr. Walsh had for years planned on building his new School of Foreign Service...on the hill overlooking the Potomac where McDonough Gymnasium now stands," writes Boyle. "Then one day during the summer of 1950, Jit Treinor, the secretary of the school, came running up to Fr. Walsh calling out that his hill was being dug out...without Fr. Walsh having known beforehand."

2. Boyle maintains that Guthrie forced Walsh to turn over $1.3 million in development funds (approximately $10 million in 2017 dollars) to Guthrie's control. A 1969 article claimed that the University treasurer, a fellow Jesuit, arrived at Fr. Walsh's office over a holiday weekend with a wheelbarrow to "unceremoniously clean out the SFS treasury."

"The operation was performed so crudely that several people remember Fr. Walsh remarking that what he found most offensive about the entire integration process was the manner in which it was accomplished," Boyle wrote.

"They came like some gangsters in the middle of the night," Walsh told a confidant.

At the close of the spring 1952 semester, the 50 year old Guthrie left campus for what was variously termed as a vacation or a leave of absence. Rev. Yates recalled it as "a break in his health, triggered perhaps by opposition to certain changes." Boyle is less forgiving, suggesting Guthrie "had absconded to Florida in a fit of concupiscence".

The leave continued through June, July, and August. By early September, Georgetown opened the fall semester without its president on campus and no news as to his whereabouts.

Five weeks later, and for reasons never publicly disclosed, Guthrie had still not returned. Perhaps seeking to avoid public speculation about the whereabouts of an absentee president, a letter on Oct. 9, 1952 delivered from the Jesuit Superior General in Rome summarily appointed Rev. Edward Bunn, S.J. as president, effective immediately and without further comment. Without fanfare, Hunter Guthrie's tenure at Georgetown was over.

The local newspapers dutifully noted Bunn's arrival and pursued nothing further. The 1953 issue of the Georgetown yearbook made no mention of Guthrie whatsoever. The only reference to Guthrie was an uncredited picture of the ex-president, in full cassock and biretta, sitting at an 1951 intramural football game, with a sly caption that must have slipped past the Jesuit moderator. It read: "One of the sport's more ardent fans gets a better view from the bench."

Curran noted that "there is both written and oral evidence that bears out the explanation that more than concern for his health was behind Guthrie's sudden and highly secret resignation." Further disclosure of such evidence, however, was never elaborated.

Hunter Guthrie returned from Florida and was quietly reassigned to St. Joseph's University in the fall of 1952. He held no administrative or executive leadership during a 20 year tenure there, serving instead as a book editor.

The decision to end major college football at Georgetown began a 20 year deemphasis of athletics at the University. Intercollegiate football was replaced by a series of organized class intramural games, with helmets and equipment left over from its big-time days. In an era when Catholic schools dominated post-season participation ranks, Basketball earned just one NIT bid over the next two decades, while baseball (an indirect beneficiary of football athletes playing a spring sport) managed one winning season from 1952 to 1970. Even today, Georgetown is one of a handful of Division I programs to have never qualified for post-season play in baseball.

Where fans once followed the exploits of Georgetown and George Washington on the gridiron, each withdrew from the local football scene. The GW program labored through the Southern Conference before finally being discontinued in 1966. As was the case in many big cities, college football had vanished from the urban landscape.

Rev. Guthrie notwithstanding, would major college football have survived at Georgetown? It could have gone the way of Fordham, whose program, much like Georgetown, relied on games at aging pro stadiums to host games. From 1946 to 1953, the Rams migrated from Yankee Stadium to the Polo Grounds to the forgotten Triborough Stadium on Randall's Island as crowds dwindled. The Rams' program, having inexplicably failed to hire alumnus Vince Lombardi as coach in the early 1950's, collapsed of its own weight in 1954 and returned as a club program alongside the Hoyas a decade later.

It could also have been the next Holy Cross. The Crusaders were a Division I-A program into the 1980's, but were never bowl contenders and its opponents were largely left among the Ivy League and New England colleges. The regional focus allowed Holy Cross to move into the Colonial (Patriot) League without a major shock to the school's football fortunes, with its best days firmly behind them.

It could have even been Boston College, where the formation of the Big East Conference elevated the entire program. The signing of QB Doug Flutie (who turned down an offer from Holy Cross) carried the Eagles to the 1985 Cotton Bowl and cemented the school as the nation's only Jesuit team at the highest levels of the sport.

But beyond what-ifs, football was never strategically managed at Georgetown. It was asked to be a money-maker for the athletic department, yet Georgetown scheduled as few as two home games a year. Regional, fan-friendly rivalries such as Virginia, Virginia Tech, and Penn State were eschewed for cross-country dates with the likes of Denver, Tulsa, and Detroit, none of which were of any local interest. Scheduling home games on Friday evenings did little to gain any local interest.

This was also the era where Maryland supplanted Georgetown in interests of the Washington media. Jim Tatum took the Terrapins from a below-average Southern Conference program to the AP national title in just seven years, and in doing so positioned Maryland for the pending realignment into the Atlantic Coast Conference in 1954. Had Maryland not been as proficient, the ACC would have likely chosen William & Mary and left Maryland, the most distant of the Southern Conference schools, to become an Eastern independent alongside West Virginia, Pitt, and Penn State.

Rent abatement, regional scheduling, and the arrival of television might have provided Georgetown the ability to provide the bridge to a future home at RFK Stadium within a decade and to support a program that could have looked very much different than its current formation, which in some ways is the progeny of Guthrie's decision. When Georgetown University president Jack DeGioia publicly opposed football scholarships in 2011, his words echoed that of his predecessors, none of which repudiated Guthrie.

"I'm not supportive of moving to a scholarship program and I'm not supportive that Georgetown would follow the move that Fordham did and go to 63 scholarships," he said. It's just very expensive and I don't think it's commensurate in who we are and in our aspirations for our athletic program."

DeGioia isn't opposed to athletic scholarships--it offers over 120 of them across multiple sports. He isn't opposed to football. But he is opposed to athletic scholarships for football, largely in the stare decisis of a decision made 65 years ago.

Joseph Hunter Guthrie, S.J. died in 1974 and is buried at the Jesuit cemetery on Georgetown's campus. The cemetery, adjacent to Cooper Field on its west (the modern home of Georgetown football) and the Intercultural Center to its north (the modern home of the School of Foreign Service), is a juxtaposition of the two issues that intersected a brief but controversial tenure at Georgetown.